Author | M. Martínez Euklidiadas

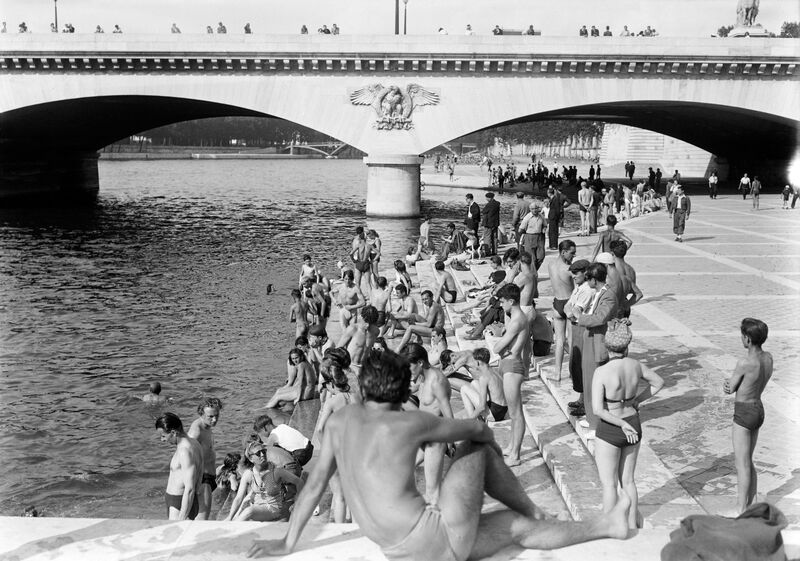

Water is highly likely to be the most challenging resource of our immediate future. From 2020 to 2022, 202 water conflicts were recorded in the world and half the global population faced water scarcity, according to the IPCC. While cities are experiencing extreme weather events, which have doubled in the past 20 years. Can cities harvest rainwater to prevent it from destroying the soil and in turn, provide the population and crops with water? Clue: absolutely.

Disconnecting rainwater downpipes, a new system for harvesting rainwater

In 1993, the US city of Portland started its successful Downspout Disconnection Program, a residential rainwater harvesting system. Instead of sending rainwater directly to the gray channels and infrastructure, it was used to harvest water in household deposits or redirect the flow to green areas capable of absorbing the surplus water.

The project was a resounding success. Surface runoff was reduced, it prevented aquifers from being drained to maintain some green areas and gray water infrastructure and water channels did not have to be increased because they were less saturated. Everyone wins.

Water courts: better than storm tanks for harvesting rainwater in cities

A storm tank is a large-volume concrete tank typically located underground and slightly impermeable. Its function is to store water during periods of heavy rainfall, to serve as a buffer during floods. But storm tanks are normally extremely expensive, very invasive with streams and biodiversity and particularly polluting. What is the alternative?

In 2011, Rotterdam built a rainwater retention system in the Benthemplein square, which is now known as the water square. The square, which is low lying and looks like a large deposit at ground level, contains basketball and volleyball courts, tiered seating or skateboarding rinks. However, during heavy rainfall, this entire space becomes flooded, adapting the use of the square to the seasonal cycles of water. This water is then fed to the network of water treatment systems.

The sponge city of Wuhan, coexisting with rain

Wuhan, the capital of the province of Hubei and known as ‘the city of one hundred lakes’, hit global news headlines due to COVID-19, but before this health emergency, the mega-city was working in favor of the sponge city concept. In fact, it is China’s flagship city for this concept, which it exports to the world.

China is characterized by water bodies and a history of flooding. Under this paradigm, cities like Wuhan are strengthening the natural foundations of the capital thanks to Nature based Solutions (NbS), which enable surplus water to be absorbed. And they are achieving it.

Creating rivers, creating rain: how to harvest rain and snow upstream from the city

In 1982, the couple formed by Josiah Austin and Valer Austin Clark began placing medium-sized rocks in dry catchment areas. Less than a decade later, reasonably large ponds had formed full of life, and a dense network of streams now cuts through the valley. There are a growing number of associated scientific articles. Could this be a way of providing cities with water? It could be if this form of basic infrastructure is located upstream of the cities.

The short water cycle consists of evaporation, condensation and precipitation, which occurs within a system. And both the Austins’ method and others (for example, the demi-lune system in Kenya, Tanzania or Tenerife, among other regions) help to condense rainwater.

Images | Stephen Fang, Lian Tomtit