Author: Octavi de la Varga, Secretary General at Metropolis

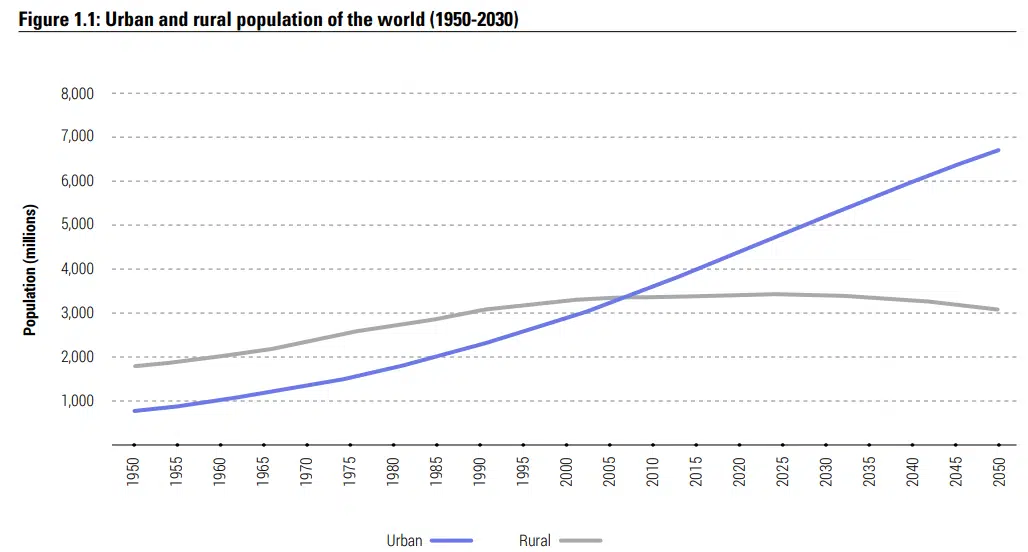

The explosion of intermediary cities all around the globe and the continuous expansion of metropolitan spaces is one of the main features of the 21st century. For many years cities and metropolitan spaces have been designed quite often thinking in terms of big infrastructures, beauty and financial return. And then, suddenly the Covid-19 pandemic turned up, leaving the world in standstill. The lockdowns forced us to see our cities and take part in public life via the internet (for those who had the means!) or through the windows. At this point many dwellers discovered the importance of a reality that we take for granted: public space.

As we highlight in our "Call to rethink metropolitan spaces", the pandemic has not probably brought new challenges at the urban level, but has made us confront the contradictions, inequalities and problems of our current urban realities.

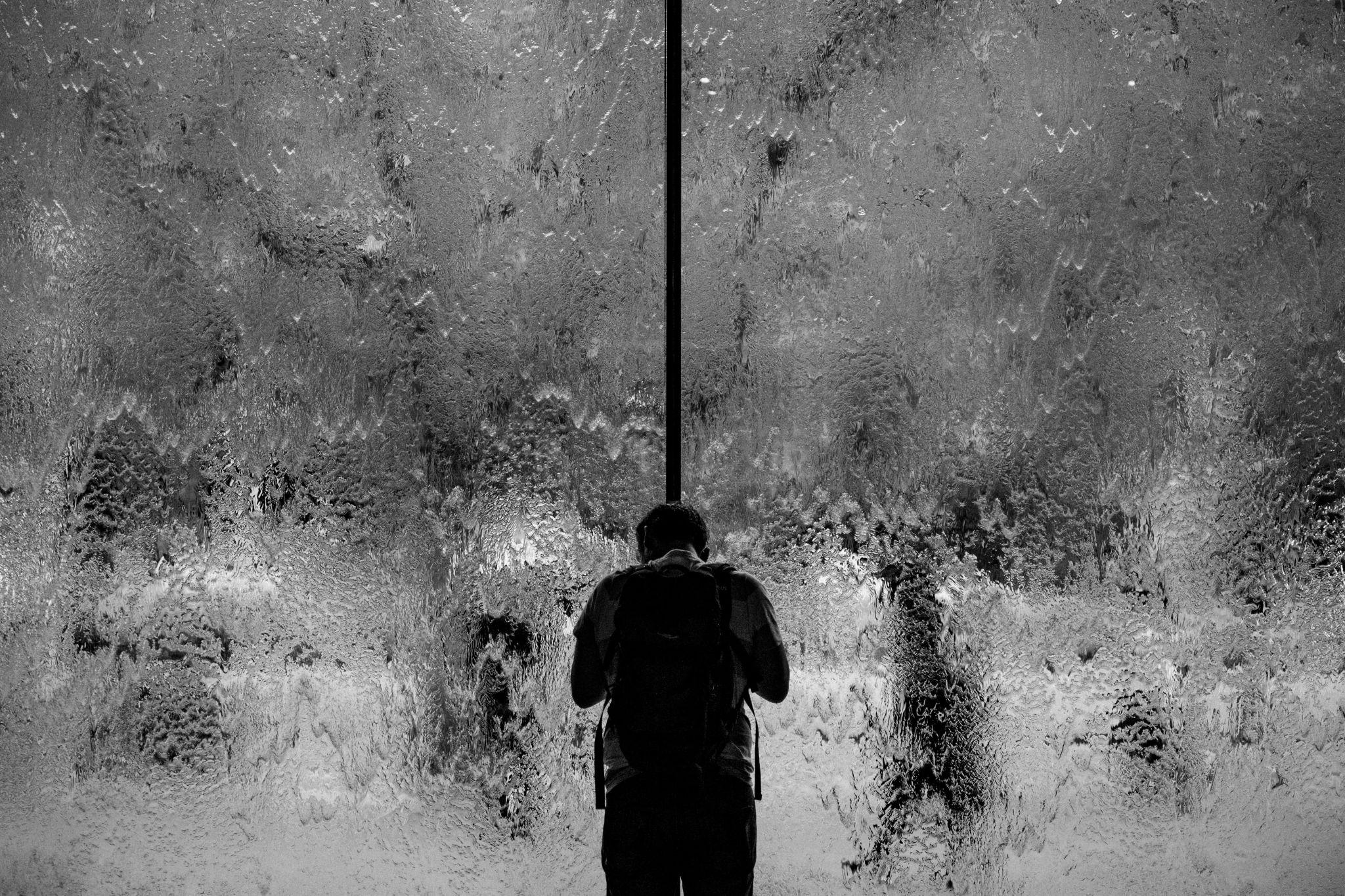

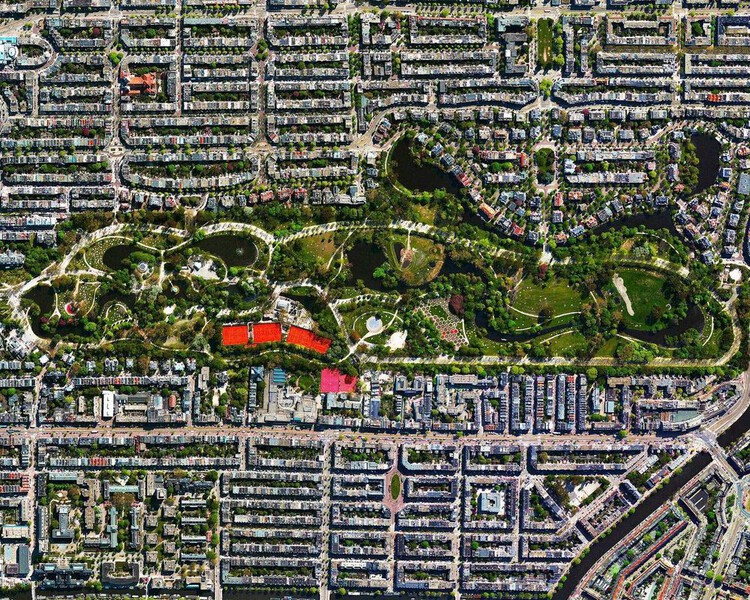

The quality of public space has become synonymous with quality of life. It is where you can experience the true soul of a city. You just need to look at what is happening there, during daylight and night: are children playing outside; can women move around safely? Are there green areas? Are streets and pathways accessible? Are cultural and economic activities being developed? We are talking here about the uses and ownership of public space.

This is not something new. It is interesting to highlight what professor Mary P. Ryan points out in her book "Civic wars: reflecting on public life in American Cities". According to her, they became less public, less democratic and visibly scarred by racial bigotry. What is surprising is that she is referring to the 19th Century. But her words could perfectly resonate regarding current urban life in public spaces in many cities around the world. Public space in the 21st century has become increasingly less public, less democratic and visible scarred by bigotry against diversity.

The previous is happening at the same time that civic disengagement and what I dare to call "urban rage" (expressed in different ways and for different reasons) is expressed in public spaces from Hong-Kong to Barcelona; from Paris to Santiago de Chile; from Bogota to Ottawa; from Johannesburg to Tehran.

As said at the beginning, those issues were already there, but the pandemic has exacerbated. The health, social and economic problems left in the pandemic seem to have shaped a process of city transformation in which all people’s interests and experiences are moulding urban planning processes. However, this is compounded when the consequences that this new disease has had on the dwellers living in large urban agglomerations are in no way contained within established jurisdictional and/or municipal boundaries.

We are talking about discontinuous, decentralised and polycentric urban spaces that generate new metropolitan environments where people live, work, shop and use services from different jurisdictions throughout a single day. Thinking about public spaces in a metropolitan context or scale can help urban planners create better, healthier and greener public spaces more equal, inclusive and accessible for all. At the end of the day, thinking in terms of public space in a city or in a metropolitan context means to think in terms of people’s needs and urban design which places human beings at the centre.

Tactical urbanism can provide urban leaders with appropriate solutions. Although there is a risk in thinking that the profound transformations that are needed to respond to the foregoing can be easily sorted out by just developing tactical urbanism interventions and bringing nature back into our urban areas.

Eventually, the debate around public space cannot take place without taking other urban debates. In particular mobility, housing and/or the digital disruption. And the role we want dwellers to play in not only shaping all these policies, but implementing and "enjoying them".

Extremely critical is the issue of the digital disruption, regarding public space, on two fields: the impact of the new economic and distribution models; and data generation.

The economic and distribution models that are turning up thanks to the fast-changing technologies are shaping our cities and metropolitan spaces; which again leads us to the question of who owns the public space and who can make the most of it. Additionally, these new businesses that make use of public space need to live together with traditional local businesses (e.g. open markets, terraces…). Stressing the relationship with business owners, users of the services and dwellers.

The other issue brought by the digital disruption is the generation of data by dwellers that are in the public space. No one will question that we need data to gain efficiencies and to better shape that public space, but at the same time there is a certain risk that instead of dwellers, we end up becoming a commodity.

Probably, the words of professor Mary P. Ryan regarding USA cities in the 19th century, that I have quoted at the beginning best represent the risks that cities and metropolitan spaces had to face during each period of history. The difference may be related to the specific challenges and the fast transformation of our urban realities. We do not have a solution that suits all realities, but what we know for certain is that solutions will only last and be adequate if they are people oriented.

Images | Tyler Gooding, Tom Barrett, Josh Appel