Author | Tania Alonso In less than 30 years, Medellin has gone from being the most dangerous city in the world to one of the most modern and organised cities in Colombia and Latin America.

In 1991, Medellin’s crime rate was headline news around the world with 381 homicides per 100,000 people. Today, after years of transformation, Medellin has won prestigious awards including the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize, referred to as the “Nobel Prize” for urban development. The capital of Antioquia has become a model of innovation and inclusive growth, and an example of how urban-planning can transform the spirit and life of a city.

Reduction of crime and violence in Medellin

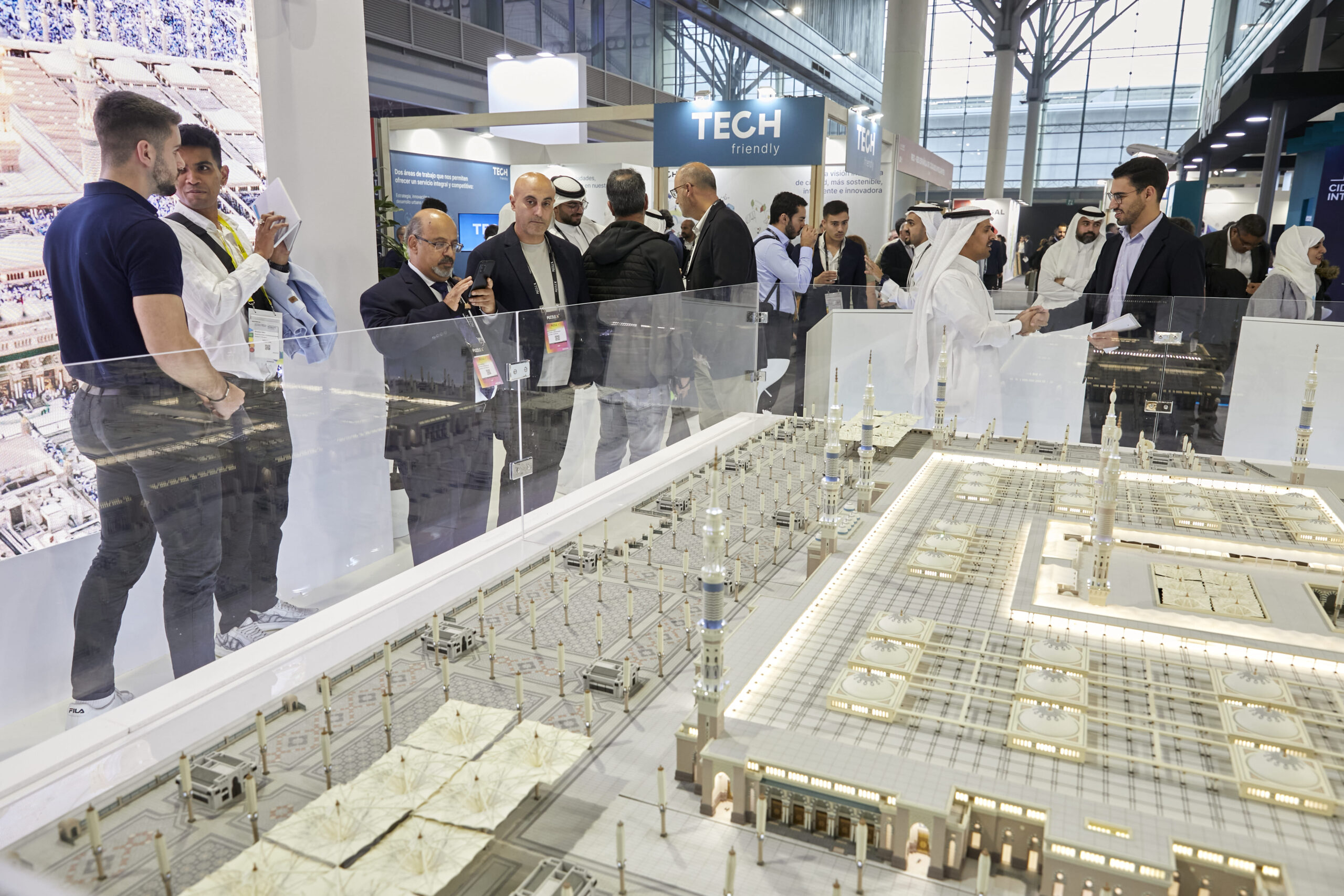

Colombia’s recent history has been marked by the activities of guerrillas, militia and drug traffickers. In Medellin, the latter were represented by the world’s most notorious drug lord, Pablo Escobar. During the bloodiest years of the drug war, the capital of Antioquia recorded incidents including murders or kidnappings every day of the year. In 1991, 6,809 deaths by homicide were recorded.The transformation of Medellin into the city it is today, a safe, inclusive and egalitarian city, was gradual, but constant. And it was based, to a large extent, on the transformation of its organisation and its infrastructures.The orography of Medellin, as with so many other areas of Colombia, is tricky. The city is located on the slopes of the Andes Mountains, at an elevation of 1,500 metres above sea level. Some of its neighbourhoods, built on steep hillsides and in hard-to-reach areas, soon became the base for armed gangs and groups.Fostering the inclusion of these areas was crucial. And, in fact, it was one of the first measures implemented by the Medellin leaders, to transform the city.

Medellin metrocable: public transport between the mountains

One of the main solutions was to install a cable car system communicating isolated areas of the city with one another, and with the subway and bus networks. This system has enabled neighbourhoods that are isolated from the centre to be accessed in a matter of minutes. Another government initiative was to install outdoor escalators to facilitate mobility in the most isolated neighbourhoods located far from the main subway lines. For example, those in Comuna 13. This neighbourhood, established in the 50s by families fleeing from the violence in rural areas, was, for a long time, the most dangerous neighbourhood in Medellin, as a result of the activities of drug traffickers, guerrilla groups, militia and criminal gangs.Today, the “Las Independencias” neighbourhood (part of Comuna 13), has abandoned its troubled past and it is now one of the city’s most popular tourist destinations. Behind this transformation are the initiatives of the residents themselves (who changed weapons for cultural and social activities) and those of the city council. Medellin’s escalators, which enable mobility and communication with the rest of the city, have replaced areas with up to 350 steps.

Another government initiative was to install outdoor escalators to facilitate mobility in the most isolated neighbourhoods located far from the main subway lines. For example, those in Comuna 13. This neighbourhood, established in the 50s by families fleeing from the violence in rural areas, was, for a long time, the most dangerous neighbourhood in Medellin, as a result of the activities of drug traffickers, guerrilla groups, militia and criminal gangs.Today, the “Las Independencias” neighbourhood (part of Comuna 13), has abandoned its troubled past and it is now one of the city’s most popular tourist destinations. Behind this transformation are the initiatives of the residents themselves (who changed weapons for cultural and social activities) and those of the city council. Medellin’s escalators, which enable mobility and communication with the rest of the city, have replaced areas with up to 350 steps.

Medellin, green and smart

Today, the city is focusing on making these pubic transport systems greener and more sustainable, in line with other initiatives carried out in recent years. One of the most representative symbols of the green transformation of Medellin, is the Antioquia University buildings: the “Morro de Moravia”This site was used as a rubbish dump between 1972 and 1984. During its initial years, up to 100 tonnes of rubbish per day would be dumped there. Despite this, and, as with the Comuna 13 neighbourhood during the 50s, hundreds of families moved to the Moravia neighbourhood in the 70s, fleeing from the conflicts across the country. Many of them settled on the rubbish dump site, where they could recycle and use the waste. In just a few years, over 35,000 people were living there, where they built houses, huts and all sorts of buildings amid the rubbish.This situation lasted until 2008, when the area was decontaminated. At that point, most of the families were relocated. Some of them had already moved in the 90s to the Pablo Escobar neighbourhood, where the capo had built 400 houses for those affected by a fire in Moravia.Other families, however, are still living in the area, which no longer has the limitations of the past. One of the city’s largest urban parks is now located where the rubbish dumb once stood. The rubbish was buried under 40,000 metres of trails, nature and spaces for the community.

The 30 green belts

Another recent environmental project in the city involved the construction of 18 tree-lined lanes and 12 waterways: the 30 green belts. The aim is to cool the environment naturally, improve biodiversity and reduce air pollution.“This intervention has enabled us to reduce the temperature by two degrees and citizens are already feeling it”, according to the city mayor, Federico Gutiérrez Zuluaga.

Data and libraries to improve inclusivity

With the aim of improving social equity and economic competitiveness, Medellin is also firmly committed to culture and education. Over the years, the city council has extended its network of public libraries in order to reach areas with a more troubled past.As part of an urban planning exercise, many of these libraries and also schools, were placed near to subway stations. Likewise, parks and sports facilities were also integrated in the areas surrounding the cable car stations.In addition to all these initiatives, the Medellin city council wants to convert the city into a smart entity based on data. “We are creating public and private open data strategies, cocreation platforms and citizen services and free internet access points across the entire city”, the mayor of Medellin explained. “We are connecting citizens with culture and technology, giving them a leading and an active role in the construction of their city”.The initiatives to make Medellin a city based on data and driven by innovation, include MiMedellin or Medata. Both have a common objective: to improve the way the city works and the quality of life of its citizens. Goals that follow on from those initiated in the 90s, when Medellin was not known for its plans for the future.Images | Daniel Vargas, Quinntheislander