Author | Jaime Ramos

The need to design inclusive cities is becoming increasingly clear across the globe. However, not all urban models being designed today meet this objective, particularly regarding disability.

It could be said that we have a historic debt in terms of disability. If we study the past, only a few cities wanted to understand that it was not enough to apply a Renaissance standard in the strict sense to the development of public services.

It has taken a long time to understand the benefits of placing humans as the standard measure of all things. Now it is time to think about… which human to use as a standard?

15 % of the global population

It is not just a case of positive discrimination toward certain minority groups. The dilemma offers a multifaceted perspective, because disability forms part of our human DNA and merges in common collectives.

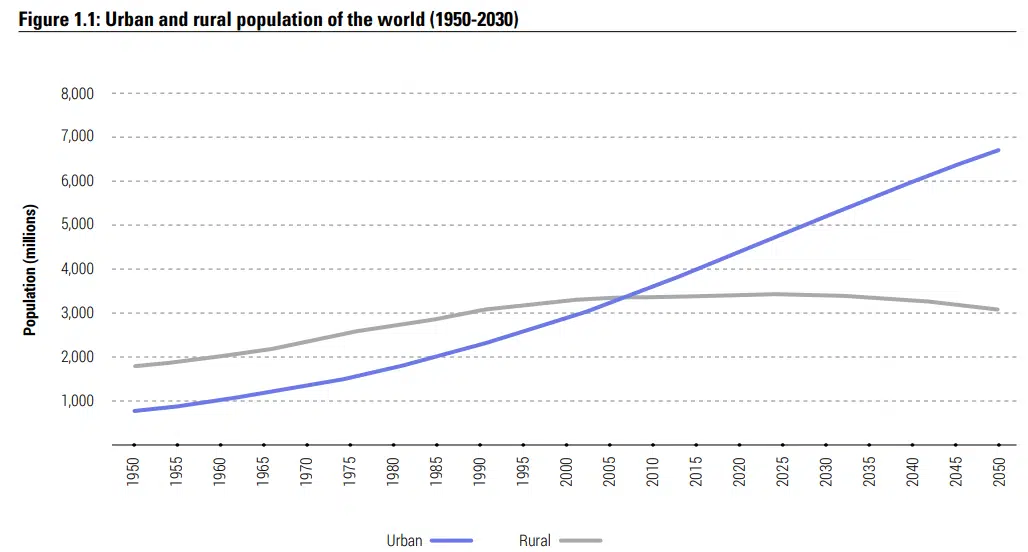

According to the UN, it is estimated that 1 billion people, i.e. approximately 15% of the world’s population, lives with some form of disability. The phenomenon is associated, to a large extent, with age. UN data also indicate that around half (46%) of people aged 60 years and above in the world have some form of disability.

If, in addition to this, we take into account the unwavering demographic trend in which we live, with populations aging at a staggering rate (if in 1960, 5% of the world’s population was aged 65 years or over, today that figure stands at 9%), we will realize that we cannot allow ourselves the luxury of decades gone by.

Solutions for each type of disability

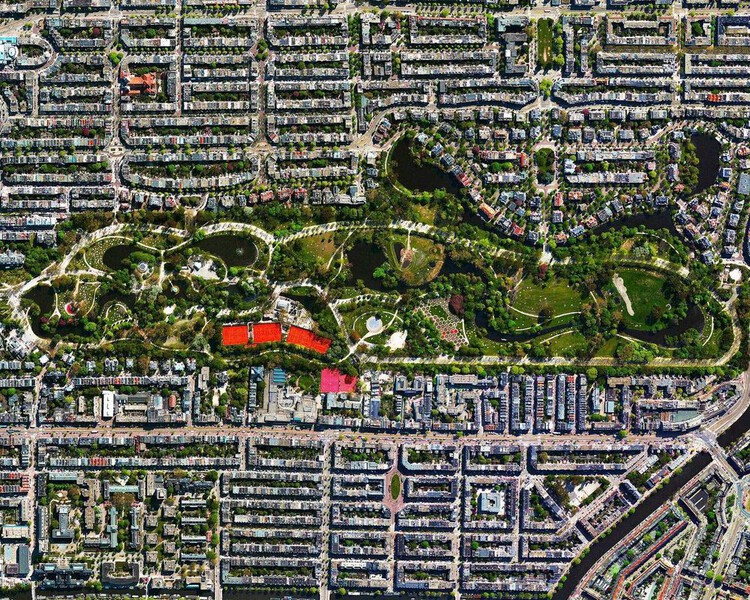

Aging is one factor, but not the core of the matter. The formula consists in looking to cities that know how to channel the advantages of technology toward the entire population.

The effectiveness of an urban economic model based on social Darwinism belongs in the past. We are now in a time of technological maturity that must be applied to the social orbit to do away with the allegorical people-devouring incinerators invented by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World.

The goal is to take action in order to facilitate the way for disabled people by implementing, not only precise infrastructures, but also specific digital developments. To do so, each of the sensory, cognitive and mobility scenarios must play a part in urban planning.

To achieve this, Global Initiative for Inclusive Information and Communication Technologies (G3ict) has launched the Smart Cities for all initiative. The aim is to establish and define the priorities of digital inclusion at a global level, in collaboration with institutions and multinationals.

This agency reveals alarming discrimination statistics. Up to 60% of global experts believe that smart cities are failing disabled people.

And what is more serious, the digital arena is generating more differences. In the United States, 23% of people with disabilities never go on online. This contrasts with the national average of 8%. Therefore, promoting the inclusive growth of ICT (Information and communications technology) has become an essential subject.

Wheelchair friendly cities

Overcoming physical and digital barriers, requires a personalized treatment in the case of disabled persons. Today we can find particular solutions in a few specific places based on each group.

This is the case with the development of apps that aim to connect infrastructures and connectivity for people in wheelchairs. AXS Map or Wheelmap were created with that in mind and are designed to identify points that facilitate wheelchair access and which do not.

These types of initiatives, which stemmed from a community spirit and which can be extremely powerful in terms of doing away with discrimination, are used by those in charge of urban planning.

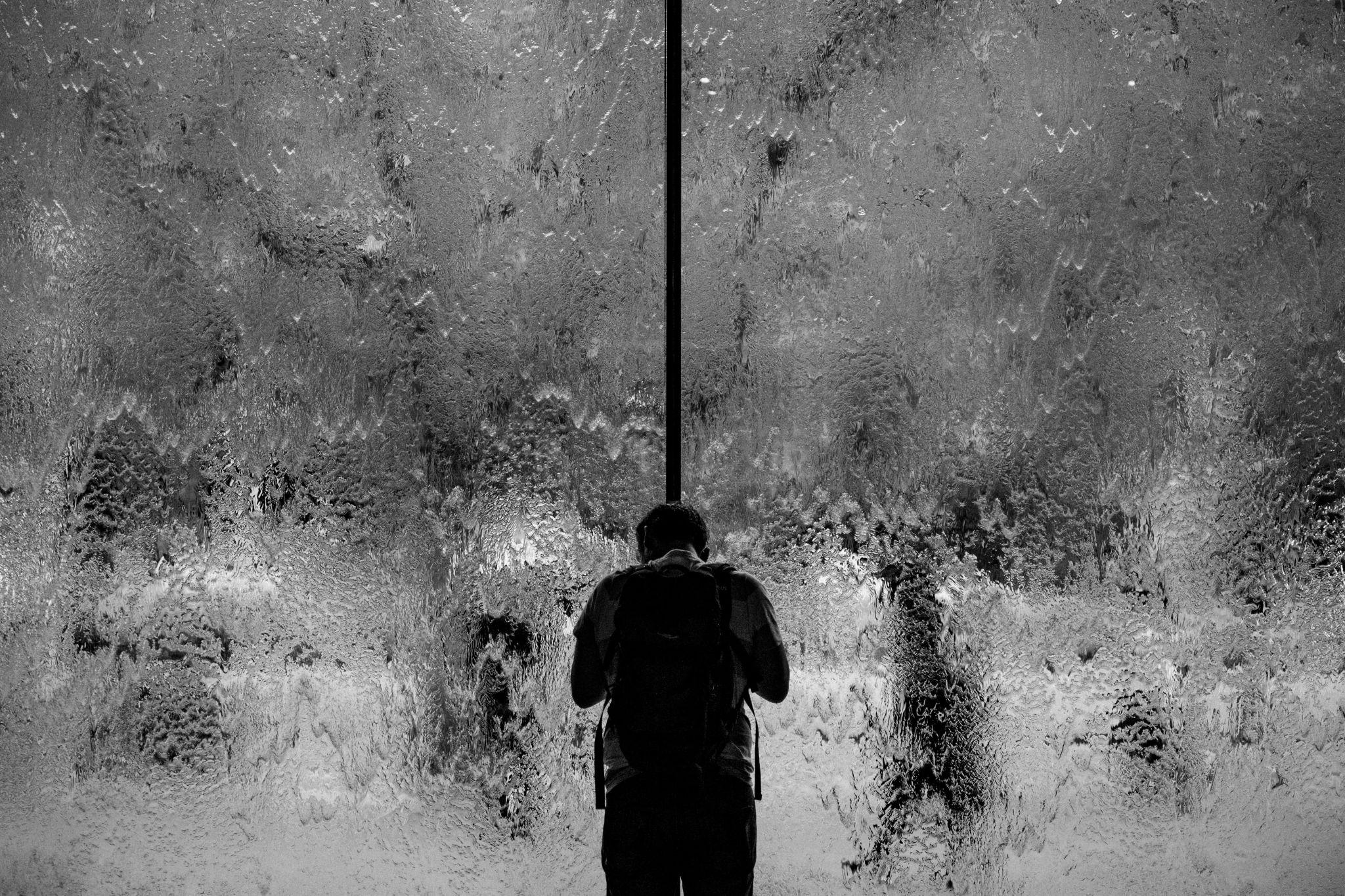

Cities made visible to the blind

Similar responses have emerged in other areas, such as initiatives for blind people. Advances in technology is Living Map’s raison d’être in the United Kingdom.

The company designs specific developments digitalizing positioning, routes and geolocation for visually impaired people. This company points out that accessibility has been integrated in architectural spaces of cities; however, the orientation and navigation of these are still a challenge.

To combat this, they have designed solutions such as the distribution of a network of electronic markers across the city. These are points that send signals via Smartphones or to digital devices such as virtual voice assistants, so a visually impaired person can receive personalized acoustic information, or in the way of a vibration, of the different physical events of a city. This will enable them to know when a bus is approaching their bus stop.

A similar innovation was implemented a couple of years ago in Melbourne with Melba. It consists of an app that synchronizes the city’s open data with the virtual assistants such as Google’s Siri; and Amazon’s Alexa. Melba was complemented at the time with ClearPath, dedicated to mobility; and Eatability, focusing on a restaurant rating system in the city based on the physical, sensory and cognitive inclusion services they offer.

How urban areas can facilitate life for people with autism

The SweetWater Spectrum model in California is a universal example of architectural and urban development adaptation. The neighborhood was designed and molded taking into account the physical and intellectual requirements of its residents.

In this case, people with autism find a community atmosphere with their development in mind. Given the specific sensitivity derived from the autistic spectrum, the aim has been to promote a sense of calm in each corner of the neighborhood.

Facilities like these cannot be the exception. Statistics remind us that 1 in 88 American children are diagnosed with this disability, which is on the rise today.

This increase in the number of people with autism leads us to also reflect on the origin of some disabilities. Scientists have already established an __empirical link between the level of pollution in cities and autism.

Situations like this prove, once again, the complex imbrication between issues such as sustainability, social inclusion and urban implementation of technology. This inclusion requires the concept of barrier to be redefined, taking into account all the variables, both physical and digital. That is why now, more than ever, a more humanist and inclusive perspective in terms of planning standards of cities is required.

Images | iStock/photographer, iStock/Ratth, iStock/RomanBabakin, iStock/Halfpoint, iStock/Tero Vesalainen, iStock/SerrNovik