Author | Tania Alonso In May 1991, the town council of Fano (Italy) organised a week dedicated to children, which would change the city forever. Children and experts took part in conferences, exhibitions and meetings, all revolving around a common point: the idea of making children the focus of policies. On the last day, a Sunday, the streets were closed to traffic so the children could play.They were able to carry out this project with the help of Francesco Tonucci, a local educational psychologist, thinker and illustrator. When the town council decided that the event should be held again, Francesco Tonucci accepted, with the condition that the initiative had to continue over time, and not just be a one-off event.That is how The City of Children began, a project aimed at making children the focus of the city and town-planning. A solution that has served to radically transform cities. Almost 30 years since the first experience in Fano, over 200 cities around the world now take part in the network, granting children an active role in governance and returning the urban space to them, which they need in order to enjoy their city just as adults do.

The City of Children was designed with the aim of transforming the way we use cities. What is this initiative based on?

It is a change of perspective that came about from a political, social, cultural and moral analysis of what has happened in cities in recent decades, since the Second World War. After the conflict, cities were destroyed and needed to be rebuilt. This is a very interesting process that is repeated after every disaster: when there is a situation of destruction, there is also the opportunity to do new things.The decision made in western countries was to rebuild the cities not for everyone, rather just with the needs of one particular citizen in mind, which I define as an adult, male, worker. The proposal behind the movement is simple: replace this citizen in city centres with a boy or a girl.

Why children?

This idea was interpreted as a provocation, but it is a choice that makes moral, scientific and legal sense. Moral because we (and I am speaking on behalf of the adult, male, worker) have reserved the power of almost everything for ourselves and we have managed it very badly. We do not deserve it. Greta Thunberg is right when she says: “How could you? How dare you?” It is a very clear statement: you have really messed up, you have restricted our expectations.

The second motive is scientific. Last century, science and neuroscience helped us understand that what happens in childhood is vitally important. Neuronal activity during a child’s initial years is never repeated in the same way during the rest of their life. Therefore, taking care of children is taking care of the future and the present.Regarding the legal aspect, this is when the Convention on the Rights of the Child come into play, which was signed 30 years ago. It put forward a new topic, which I believe was revolutionary: children as citizens. For the first time, they were considered to be citizens with rights. Article 12 states that children have the right to express their opinion whenever decisions are made that affect them and their opinion must be taken into account. It is an impressive commitment, taken 30 years ago by the owners of the world, the members of the United Nations.

How is this right set out in the City of Children?

Our project has two central themes. The first is the right of children to take part in the governance of their city, their school or wherever they are located. This proposal does not involve a banal and naive way of thinking that they know more, rather it is based on the idea that children can offer diversity in our policies. Children are different to us: they see the world from a different height and not just physically.Adults need to make the effort and make a conscious point of asking them what they think. How they see the city, what, in their opinion, does not work. I don’t know, I can’t remember my childhood. Children, with other perspectives, suggest things that we no longer consider to be important.The second is the right to autonomy, which is also a way of taking part. Children have the right to take part with their physical presence in city life, independently and not just as accompanied children.

We don’t let them out on the streets because we think they are dangerous; they must be dangerous because there aren’t any children on the streets. If there are children alone on the streets it means adults in the neighbourhood have to be responsible Pay attention, worry, keep an eye on them, but from afar, not by holding their hand. This builds an atmosphere in which there are people who are alert, meticulous, very inconvenient for delinquents. We have experiences that prove that this is the case. Where children move about with autonomy, there is more security.

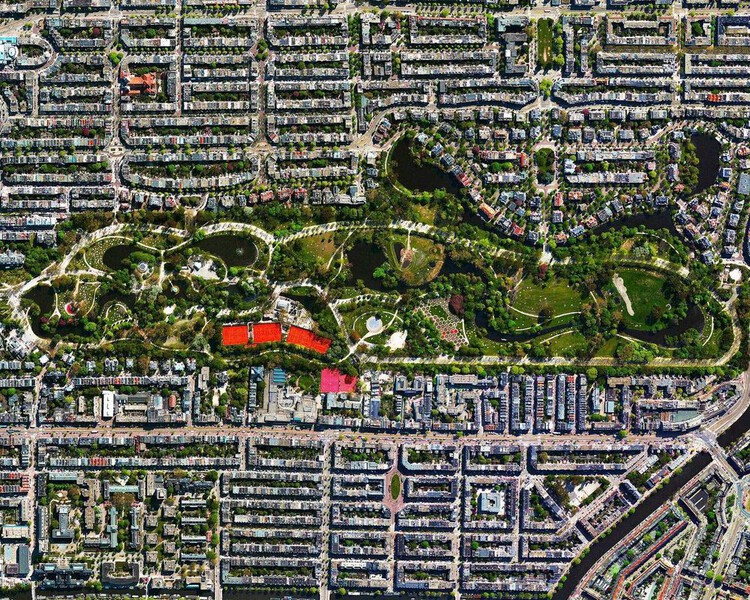

How important are pedestrian areas and green spaces to guarantee the autonomy of children?

Personally, I am not in favour of pedestrianizing areas. What I am in favour of, is sharing spaces, but respecting priorities, which are not those that we see today. The priority for our administrators is private mobility, then public transport and lastly, pedestrians or citizens that get about autonomously, such as cyclists. This results in public spaces being virtually privatised by traffic or parking spaces for private vehicles.We are not so interested in closing off areas of the city as we are in changing priorities. Returning the city to pedestrians, placing public means of transport in second place and private vehicles in third place. They should have the space available to them once the needs of pedestrians and public means of transport have been met.

How can cities be transformed in order to achieve this?

By really extending pavements, reducing the size of roads, restricting above-ground parking and creating complicated routes for private cars. It involves designing cities in a different way and returning public spaces to citizens.. In environmental terms, this has a huge impact, since pollution would drop dramatically. The health of residents would improve considerably too. The WHO says that we need to walk every day. I think that a democratic city, concerned for its present and its future, should be a city in which walking is the most convenient and easiest way to get about.

However, this is not the case in most cities. What dangers does this entail?

It greatly affects the health of citizens. Reduced life expectancy is greatly related to air pollution, a reduction in autonomous mobility and faster living, which causes stress.At the moment, much is being said of Greta Thunberg, who deserves all our attention. We think she is only referring to environmental problems, but this is not the case. Another matter, which is almost the most shameful of all, is that research from over ten years ago proves that future generations will have a shorter life expectancy than we do. This is shameful for my generation. Never before had this happened in modern history: generations have always worked to benefit future generations. If what I am saying is true, it means we have totally betrayed our role as parents and grandparents.

A fundamental principle of The City of Children is the right to play. Why is it so important and how can it be guaranteed in cities?

Playing is children’s real role, the most important duty they must fulfil. Cities must be play-friendly, but not as they are today. When children stopped being allowed to go outdoors on their own, they invented children’s parks. Spaces scattered all over cities and which are all the same and nearly always closed. When I see these spaces and I argue with administrators, mayors or architects, I always say that they were designed by people who were not lucky enough to have had a childhood.Public spaces should be the place in which children play.

From their front doors to the pavements, everything is a potential play area. It is absurd for children to go to the same place every day and play the same games and always monitored. Each game has its appropriate space, these cannot be spaces chosen by adults that no longer even remember their childhood. If we manage to get children outdoors without being accompanied by adults, we will no longer have to worry about creating these spaces.

Over 200 cities are involved in the network. Do any stand out in particular?

We have the experience of Pontevedra, a city on our network that receives international awards. In Pontevedra they have taken away the power of cars and they have given it back to the people, reducing the size of roads, extending pavements and making all zebra crossings at pavement level, so pedestrians can walk on one level and never stop. The cars have to move. This greatly reduces speed, danger, pollution and noise. Families have more peace of mind and children can recover the streets as a meeting place and somewhere to play.Other cities that have really made a difference are Rosario, in Argentina and Pesaro, in Italy. The latter has worked very hard to improve the autonomy of children. My city, Fano, is also very busy, since the children’s council has never stopped.

Do you think cities will be able to overcome their existing challenges?

They need to choose between improving or disappearing. I believe we have alternatives right now. If the environmental issue is going to reach a point of no return in 15 years, we need to make radical changes.There are cities that already believed this, such as Oslo, which has very radical projects and programmes in place to reduce pollution, or Pontevedra. These are models that should be copied. Each city has particular characteristics and must adopt different solutions, but in terms of changing or not changing, there can be no doubt. Radical changes are to be made if we want to survive.

Can technology be a solution to this issue?

Yes, of course. But it is an instrument, it will not do it alone. Using technology is a duty, waiting for things to change on or behalf is simply foolish. Images | Javier Barbancho, Charlein Gracia, Vita Marija Murenaite, Hugo Pretorius