Author | M. Martínez Euklidiadas

An icon of improvised urban planning even before it was demolished, the Walled City of Kowloon in Hong Kong, was famous for being the most densely populated place on Earth, with approximately 1,255,000 inhabitants per square kilometer in 1987. To put this into context, Tokyo, the most densely populated city on Earth, has around 6,373 inhabitants per square kilometer. However, there were not millions of inhabitants in Kowloon, but rather "just" 50,000 people squeezed into 0.26 square kilometers.

The fact that the Chinese Empire did very little to regulate constructions in the area, and that the British Empire almost completely abandoned any prior laws that were in place, or that the Japanese Empire scared off all the authorities when Japan occupied during WWII, did little to help the irrational growth of Kowloon.

The Walled City of Kowloon

The construction of Kowloon dates back to the Song dynasty (960–1279), a period characterized by the salt trade in the region. During the Roman Empire, salt, a term which the word ‘salary’ stems from, was one of the most relevant materials of the time. This small trading post enabled the Song to consolidate their power in the region. And subsequent dynasties did the same thing.

In 1898, the British Empire expanded its colony to include the region of the Kowloon complex and established a military outpost within the grounds. Regarding the urban design, Pedro Torrijos, author of the book ‘Unlikely Territories’ (2021), defined it as "a marvelous exercise of abandonment of responsibility." At the time, the small walled community of Kowloon was home to just 700 people, which dropped to 150 just one year later due to local riots.

In 1912, while the Titanic was sinking in the Atlantic, the Qing Dynasty (1644 to 1912), ruled Hong Kong and the rest of China. There was no formal opposition to the British Empire in the area (although the resulting Chinese government did reclaim its jurisdiction over the city in 1933), but it did not establish regulations to reorganize the city. With no room to grow outwards, Kowloon grew in Hong Kong the only way it could: upwards.

The birth of a lawless city

Kowloon is a persistent place. If in 1933 the local government demolished a large part of the buildings on the grounds of public disorder, by 1940, 2000 people were once again living in wooden shacks on the site, a reasonable number given the amount of land they were occupying and the scarce infrastructure in the area. An infrastructure that was about to be multiplied by one hundred, and not by the institutions.

Institutional abandonment, which had been the general theme in Kowloon, reached its highest point during the war between China and Japan (Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), and subsequently during the Second World War. There was simply no room for order and the administrations were overwhelmed or had fled, leaving the inhabitants to fend for themselves.

Conditioned by the wars, during the 1940s, Kowloon became a lawless city, taking in anyone running from the Law. In just a few years, the city doubled its population and built a complex of makeshift shacks. The few administrations that once existed were long gone. They were alone.

Then, in 1950, a fire wiped out a large number of wooden huts. Around 2,500 huts or shacks that were home to 3,500 families burned to the ground. Far from dispersing, the inhabitants decided to use structural concrete and bricks. These new materials allowed them to build upwards, which they were delighted to do. That was the beginning of the Kowloon that we are familiar with today thanks to Ian Lambot’s striking images, documenting the final years of the city in his iconic book City of Darkness.

Demolishing the urban chaos

The Triads, an organized-crime group originating in Zhengzhou, Hong Kong and Guangzhou, occupied Kowloon and controlled this curious complex for decades. In fact, in 1983, the Hong Kong police confirmed they were not able to maintain control within Kowloon. That was when plans were announced to demolish the city, a decision that was postponed for almost a decade.

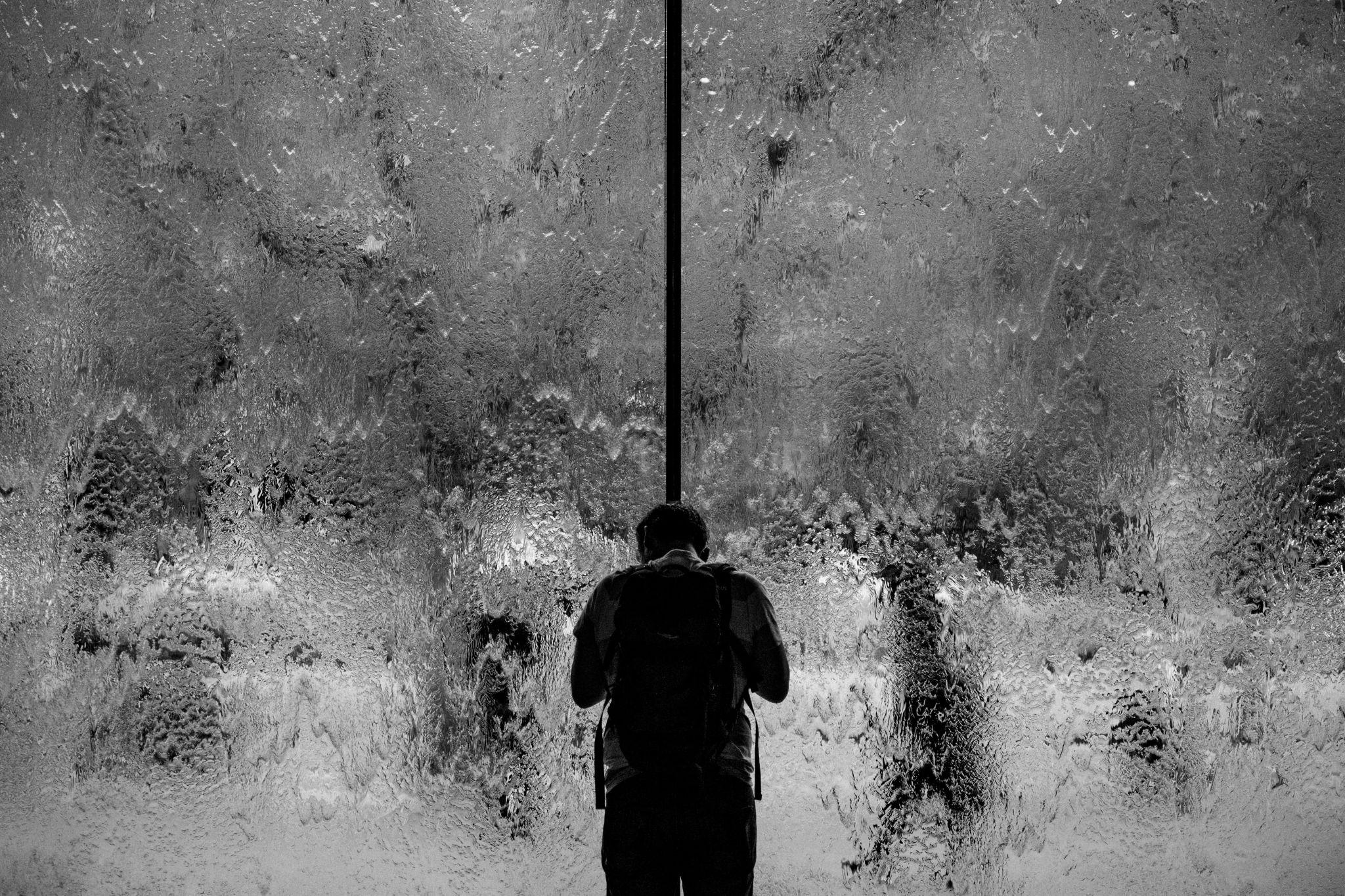

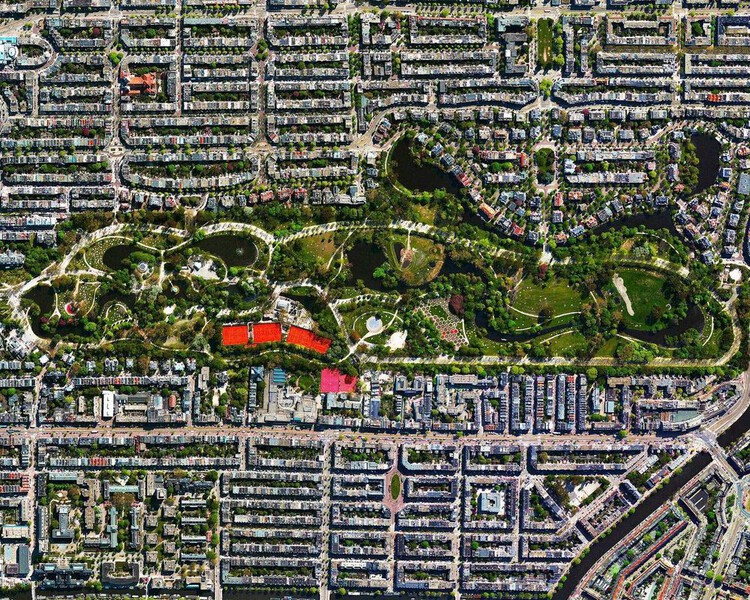

Aerial view of the Kowloon Walled City Park, old site of Kowloon.

Aerial view of the Kowloon Walled City Park, old site of Kowloon.

In March 1993, the demolition of Kowloon began, a process that took almost a whole year, and experienced its fair share of local opposition. Apart from mafias, drugs, delinquents and filth, there were also families, businesses and stores in the dense city. The Kowloon Walled City Park was built on the site, a small park that emulates an old stronghold of the Qing Dynasty.

Compensation

Despite its informal status and precarious architecture, created almost with the utmost disdain towards any public code and law that didn’t fit the common sense of its inhabitants, Kowloon couldn’t be demolished overnight. Hong Kong had to provide its residents with some kind of housing solution before tearing down this unique colony, and readied a HK$2.7 billion (US$350 million) compensation fund.

Nevertheless, not everybody wanted to leave. After so many decades of almost anarchic existence, some residents didn’t want to move, and had to be forcefully evicted from the citadel.

The archaic and persistent urban design of Kowloon

In reality, the city of Kowloon is not the only one of its kind. The unruly growth of cities, buildings on top of one another, without sewage systems or basic services, were prevalent in ancient times. Cities such as Ur, which dates back to the 5th millennium BC, which we tend to think of with a notoriously distorted romantic vision, were narrow, dark, dirty and crowded complexes, all packed with houses lacking any form of hygiene.

That is how most cities of Mesopotamia were: narrow, without streets or open spaces and full of nooks and crannies. Houses without windows or light that often had a hole in the roof with a ladder propped up to descend into the darkness. What was particularly striking about the city of Kowloon was that it existed for so long in a period that did not correspond to it: a form of urban design from thousands of years back, transported in time.

In 1996, years after this stronghold had been demolished by the Chinese and British authorities, a team of Japanese documentary makers published ‘Grand Panorama of the Kowloon Walled City’, with a fabulous fold-out spread featuring a detailed cross section of the city.

This cross section drawing is a fantastic reflection of the complexity of Kowloon. A far cry from the low-rise shacks or ground-level expansion. The most densely populated city in the world was a labyrinth of small corridors and staircases communicating thousands of houses in a compact and particularly live network not unlike the buildings of ancient times.

Like these, Kowloon was unhealthy, dangerous and with high crime rates. Each one of these reasons would have sentenced the construction, but all of them together had made ‘the building’ pose a serious threat to the safety of the region and of the families living in the complex. The demolition of the complex was inevitable in a world with a smart city approach.

Images | Ian Lambot, Ian Lambot, Amber Case, Wpcpey, Ian Lambot