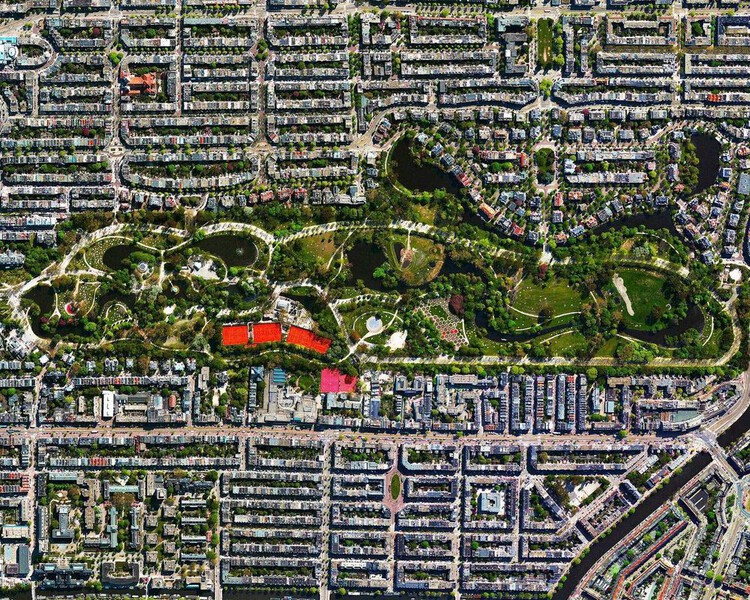

Right in the center of Buenos Aires, separated from the rest of the city by the railway tracks and in front of one of the most exclusive areas of the Argentine capital, is Barrio 31. This irregular settlement is one of the oldest in the city and home to 40,000 people.Since it emerged in the 1930s, there have been many unsuccessful attempts to eradicate it, as it occupies privileged plots of land in the heart of Buenos Aires. But the option of integrating it and converting it into another neighborhood in the city with the same rights, but also the same obligations, has come out on top. Accordingly, for five years now, it has been undergoing a considerable urban, economic and social transformation and forms part of a global study.Behind this ambitious and bold project is the secretary of Social and Urban Integration of the City of Buenos Aires, Diego Fernández. We chatted to him about the important challenge of an intervention of this kind, which shows signs of becoming an exportable model inside and outside of Argentina. The marginalization situation of Barrio 31 is changing thanks to a series of significant public initiatives.Indeed. In December 2015, with the creation of the Ministry of Social and Urban Integration of the City of Buenos Aires, we formally launched the Barrio 31 integration project. From the start we knew that, in order to tackle the different problems that existed, we needed to introduce a holistic approach. That is, work on a whole host of issues simultaneously. Our aim is to make Barrio 31 another neighborhood in the city and for its residents to be able to access the same rights and have the same responsibilities as any other inhabitant of Buenos Aires. However, in order to achieve this, we needed to form a multidisciplinary team to focus solely on the neighborhood.

"Our aim is to make Barrio 31 another neighborhood in the city"

What are the core aspects of the project? There are five: infrastructures, housing, education, health and economic development. We carry out numerous coordinated interventions in each of these and with a common element: the involvement of residents in the design and decision-making through meetings, discussions and other channels.Could you give us any specific examples?We are currently completing the construction and renovation of 100% of the neighborhood’s infrastructures -over 16,000 meters of works-, including sewage systems, rainwater drainage systems, drinking water connections, electrical grid and public lighting. In addition to optimizing its 26 public spaces.In terms of housing, i.e. the condition of the houses, we are working on two areas: on the one hand, renovating the properties, so they are all safe, accessible and suitable, and, on the other hand, we are building 1,200 new properties for families whose homes cannot be renovated.

There are five: infrastructures, housing, education, health and economic development. We carry out numerous coordinated interventions in each of these and with a common element: the involvement of residents in the design and decision-making through meetings, discussions and other channels.Could you give us any specific examples?We are currently completing the construction and renovation of 100% of the neighborhood’s infrastructures -over 16,000 meters of works-, including sewage systems, rainwater drainage systems, drinking water connections, electrical grid and public lighting. In addition to optimizing its 26 public spaces.In terms of housing, i.e. the condition of the houses, we are working on two areas: on the one hand, renovating the properties, so they are all safe, accessible and suitable, and, on the other hand, we are building 1,200 new properties for families whose homes cannot be renovated.

“We began with the construction and renovation of infrastructures and houses, to then address issues such as education, health and economic development”

We began with these core aspects for obvious reasons. With dirt tracks, the risk of disease due to the lack of adequate sewage systems and the danger of accidents due to irregular power lines, it was exceedingly difficult to tackle issues such as education or the professional development of residents.Now, can you focus on these aspects?Yes. While we are establishing the foundations in terms of infrastructures and housing, we are also working on the social and economic integration of the neighborhood so that each resident has the chance to develop.In this regard, we have built three new health centers so residents can receive primary health care close to their homes and over 18,000 inhabitants are now integrated within the healthcare system. In terms of education, we have built the María Elena Walsh complex, which is home to the new Ministry of Education headquarters, a nursery and primary school, and another one for adults. We have also completely renovated the Mugica education center, the largest in the city. We have also added a new school in the most isolated area of the neighborhood and a professional development center.Together with all these projects, we have also introduced a student school support program for dropout prevention and to improve students’ classroom experience.And in terms of the fifth core aspect of the project, the economic development of the neighborhood?This pillar is key to achieving sustainable integration. Over the years, the growth of Barrio 31 has coincided with the growth of its economy outside of the formal channels. In order to tackle this problem, we have developed the Center for Entrepreneurship and Labor Development (CeDEL), an area in which we focus on all the labor integration, training, development and support services for entrepreneurs.

In terms of education, we have built the María Elena Walsh complex, which is home to the new Ministry of Education headquarters, a nursery and primary school, and another one for adults. We have also completely renovated the Mugica education center, the largest in the city. We have also added a new school in the most isolated area of the neighborhood and a professional development center.Together with all these projects, we have also introduced a student school support program for dropout prevention and to improve students’ classroom experience.And in terms of the fifth core aspect of the project, the economic development of the neighborhood?This pillar is key to achieving sustainable integration. Over the years, the growth of Barrio 31 has coincided with the growth of its economy outside of the formal channels. In order to tackle this problem, we have developed the Center for Entrepreneurship and Labor Development (CeDEL), an area in which we focus on all the labor integration, training, development and support services for entrepreneurs. Therefore, we are working everyday with the residents who are looking for work and those wanting to develop professionally, with stores and over 50 companies that contribute within the private sector, with training, courses and, particularly, by employing the residents.An example of the success of CeDEL is that we currently have over 1,200 entrepreneurs and over half the economically active population has passed through the center.Of particular note is the aim to formalize an eminently underground economy by opening banks and a fast food restaurant.These are two examples that form part of our broader policy of commercial integration and economic development. The new restaurant is not just that, it represents 80 jobs for youngsters in the neighborhood and the banks form part of the financial formalization and inclusion efforts.

Therefore, we are working everyday with the residents who are looking for work and those wanting to develop professionally, with stores and over 50 companies that contribute within the private sector, with training, courses and, particularly, by employing the residents.An example of the success of CeDEL is that we currently have over 1,200 entrepreneurs and over half the economically active population has passed through the center.Of particular note is the aim to formalize an eminently underground economy by opening banks and a fast food restaurant.These are two examples that form part of our broader policy of commercial integration and economic development. The new restaurant is not just that, it represents 80 jobs for youngsters in the neighborhood and the banks form part of the financial formalization and inclusion efforts.

“The payment for the formalization of properties and for public services, as well as caring for spaces that belong to everyone, are key aspects of this project”

In these marginal areas integrated within the cities, there is a trend to return to old ways. Is there a need for a culture of caring for public assets?We are working on developing a citizen culture. As I said earlier, our aim is for residents to be able to access the same rights, but they must also comply with the same obligations as any other resident in the city. In this regard, the payment for the formalization of properties and for public services, as well as caring for spaces that belong to everyone, are key aspects of this project.Could this regeneration run the risk of gentrifying Barrio 31? Gentrification is a risk in any project of this type and that is why we have implemented measures to mitigate it. Firstly, as part of the property formalization process, we have reformed the Urban Planning Code to adapt it to the reality of Barrio 31. We have therefore created a specific district for the aera, with regulations regarding the use of the air space and specific limits for the accumulation of plots.

Gentrification is a risk in any project of this type and that is why we have implemented measures to mitigate it. Firstly, as part of the property formalization process, we have reformed the Urban Planning Code to adapt it to the reality of Barrio 31. We have therefore created a specific district for the aera, with regulations regarding the use of the air space and specific limits for the accumulation of plots.

“It is no longer legally possible to unify plots of land to construct much larger buildings than those that already exist”

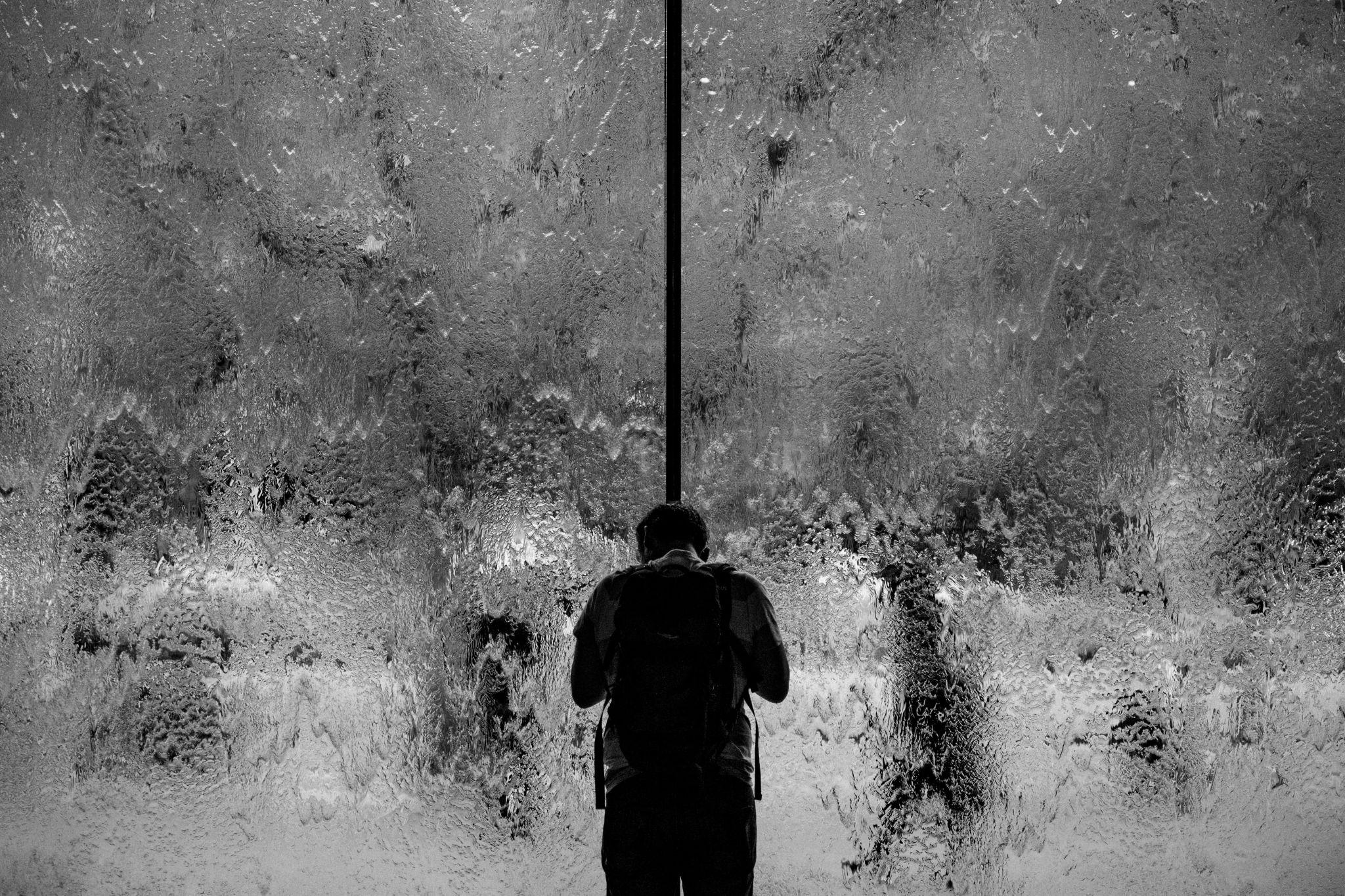

Therefore, it is no longer legally possible to unify plots of land to construct much larger buildings than those that already exist” In addition, almost the entire neighborhood has a sole residential use, i.e. only houses or small stores can be built.In a neighborhood with a history of fear of being vacated, have there been many reservations with regard to the project?It is essential to remember that Barrio 31 has existed since 1932 and that during this long period, there have been many attempts to forcefully eradicate the neighborhood. In this regard, the mistrust among residents and the State was to be expected, particularly when the approach of public policies -eradication- did not manage to resolve any of the problems that were rampant in the area.

“In order to address the mistrust of residents, the solution is to get them involved in the integration process”

In order to address the reservations and feelings of mistrust, the solution is to get the residents involved in the integration process, which is not easy. On the contrary, it generates debates, discussions and disputes, but also spaces in which everyone can express their positions, understand one another and work on finding a common ground.People come in and out of the neighborhood, but very few that live outside of it tend to access it. How can you bring together these two remarkably close, and yet, vastly different worlds? That is precisely one of our main challenges, to get residents from other neighborhoods in the city to discover Barrio 31, to walk around it and take advantage of its wide range of commercial and cultural choices on offer. We are making great progress; however, it is in no way something that will be achieved from one day to another.The arrival of the new Ministry of Education headquarters in the neighborhood is a unique aspect that is aimed in that direction: there are 2,200 workers, plus many more people who carry out procedures and who are beginning to stroll about the neighborhood. Stores are benefiting, there is more mobility and, gradually, these two worlds, which are really all part of Buenos Aires, are coming together.

That is precisely one of our main challenges, to get residents from other neighborhoods in the city to discover Barrio 31, to walk around it and take advantage of its wide range of commercial and cultural choices on offer. We are making great progress; however, it is in no way something that will be achieved from one day to another.The arrival of the new Ministry of Education headquarters in the neighborhood is a unique aspect that is aimed in that direction: there are 2,200 workers, plus many more people who carry out procedures and who are beginning to stroll about the neighborhood. Stores are benefiting, there is more mobility and, gradually, these two worlds, which are really all part of Buenos Aires, are coming together.

“We want to preserve and boost the identity of Barrio 31 in the city, not impose a new one”

In this process, Barrio 31 has a great deal to show and offer the city given its diversity, gastronomy and culture. We want to preserve and boost the identity of Barrio 31 in the city, not impose a new one.The concentration of immigrants and poor workers in settlements is common in Latin America. Is Barrio 31 an exportable model?We believe the public integration policy has the potential to be replicated in other settlements across the country and the world. In any event, it is really important to emphasize that no two informal neighborhoods are the same, and it is particularly those unique features that needs to be preserved and promoted.The main aspect to be replicated is the project’s approach and the work method, intervening in an intensive, simultaneous and participatory manner in all the different aspects.Images | Diego Fernández, Secretaría de Integración Social y Urbana de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires