Author | Lucía Burbano

If he had just stuck to designing cities, Le Corbusier would have been a frustrated urban planner without the revered status of architect that he has today. His projects to convert Barcelona, Bogota or Buenos Aires into functional and rational cities failed and only Chandigarh in India actually materialized. Why did such an admired architect fail so miserably as an urban planner? His project for Paris, the Radiant City, answers this question.

What was the Radiant City?

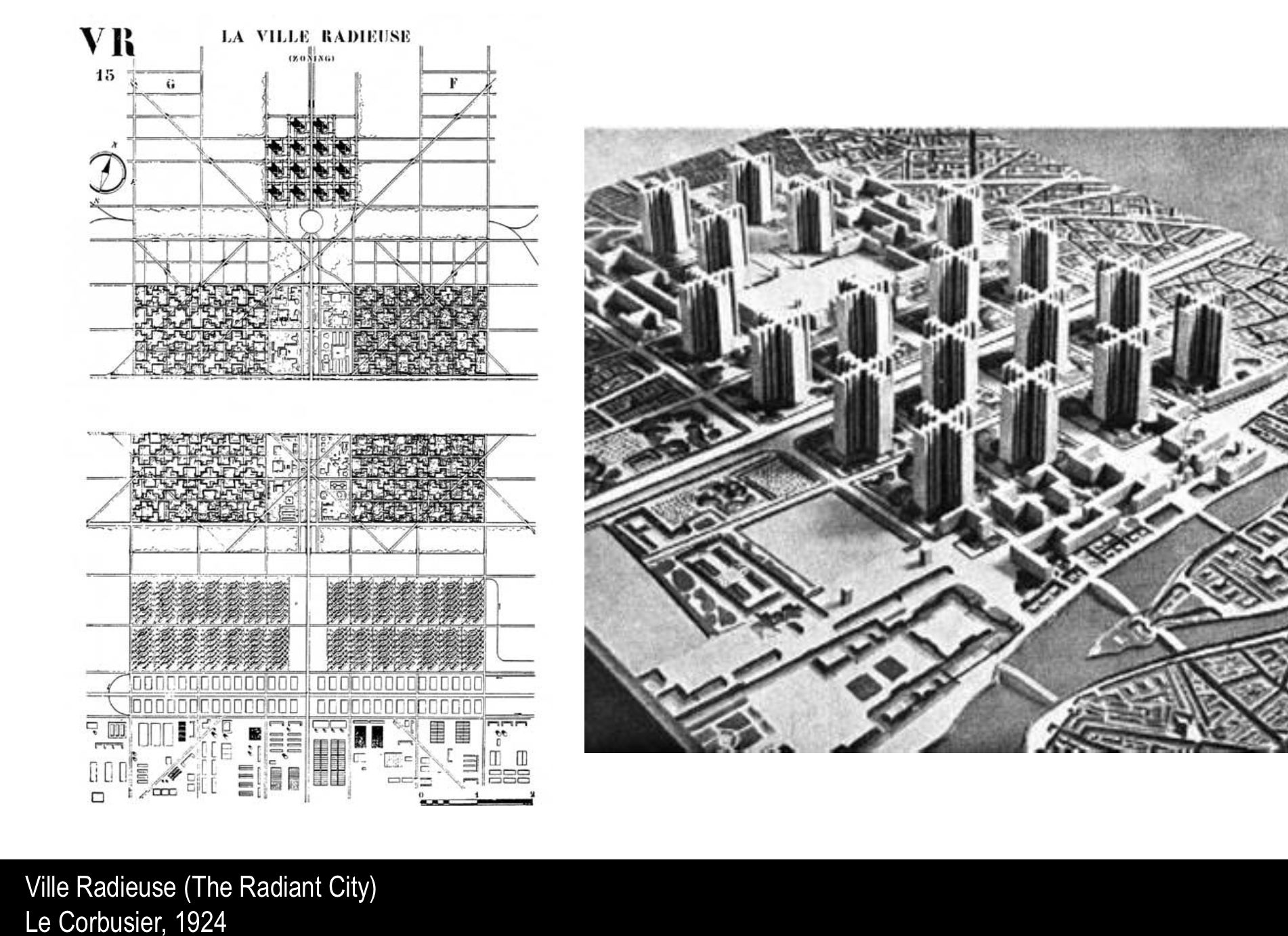

The concept of Radiant City or Ville Radieuse was an urban design project for the center of Paris, which the architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, aka Le Corbusier, first presented in the Parisian Salon d’Automne in 1922.

In the center of a completely asymmetrical masterplan were 24 cruciform skyscrapers standing 200 meters tall, intended to house businesses and hotels. Around it were residential districts for the skyscraper workers, made up of apartment buildings following his concept of unité d’habitation located in Marseille or Berlin. Each block would house 2,700 residents and would follow a mixed-use style of architecture, with a laundry, restaurant and daycare center on the ground floor and a swimming pool on the rooftop terrace.

Finally, an area was planned on the south side divided into three parts to be used for manufacturing, storage and large industries, while the north area would be used for gardens and leisure areas.

What was the purpose of the Radiant City?

Le Corbusier justifies his Radiant City concept in the book La Ville Radieuse (1935) criticizing the urban model that prevailed at the time. Let’s allow the architect himself to explain the concept: "The city of today is a dying thing because its planning is not in the proportion of geometrical one fourth. The result of a true geometrical lay-out is repetition, the result of repetition is a standard. The perfect form".

Le Corbusier had four objectives for his Ville Radieuse:

- To provide efficient communication networks.

- To ensure the enlarged, vast areas of greenery throughout the city.

- To increase access to sun.

- To reduce urban traffic.

By achieving them, he would manage to increase the urban capacity and, at the same time, improve the surroundings and efficiency of the city, as he expressed at the International Congress of Modern Architecture in 1928, which established the bases of this rational design.

Advantages of the Radiant City

The Swiss-French architect’s intentions were to favor "living, working, circulation as well as care of the body and spirit", in this order and hierarchy".

As a supporter of communism and socialist policies, Le Corbusier defended the equality of classes. One of his architectural premises was to achieve maximum functionality at minimum cost regardless of the origin and social class of users.

Modernists were the main promoters of sanitization or the curative capacity of well-lit and well-ventilated rooms. In an era in which all sorts of diseases were prevalent, this resulted in healthier and more functional dwellings and infrastructures, where garden areas, so sought after today, occupied very generous plots.

Mixed skyscrapers as a solution to urban density also formed part of this masterplan adopted by many cities to prevent the areas on the outskirts from becoming detached and disconnected from the old quarters of cities.

Lastly, the Radiant City proposed a very current concept, associated with the walkable city: the division of spaces between vehicles and pedestrians and the importance of having an exceptionally well connected public transport system to communicate the different areas that make up this idea of city.

Why did the Radiant City of Le Corbusier fail?

Le Corbusier is blamed for having an exceedingly rationalist vision of the city. His colleague and contemporary, Hugo Häring, argued that the Swiss-French architect’s design was "a proposal of an abhorrent future, organized like a "Prussian military world", orderly, aligned, disciplined, but cold".

Furthermore, according to the authors of this study, the calculations regarding the natural light that would illuminate this Radiant City did not coincide with the light conditions offered by the center of Paris. This would particularly affect the entry of daylight into the skyscrapers. A real slap in the face for what was supposed to be one of the primary incentives of Le Corbusier’s urban plan.

Another controversial point that put an end to the project was that its construction would have involved demolishing practically the whole part of central Paris, wiping out the architectural history of the city of light.

Lessons learned from failure

Although his vision of urban design did not catch on, it is important to remember that this is also the result of a very specific context, that of a world between wars, and a rationalist model that wanted to do away with the dark, unhealthy and polluted cities that existed at the beginning of the 20th century.

Despite never materializing, various useful lessons can be taken from the project and applied to contemporary cities:

Cities cannot be designed with just a set square

Cities are much more than grids made up of streets and buildings. They must include spaces that generate relationships between people, enabling spontaneity to flourish.

The city is a living ‘organism’

Cities change to adapt to new times and requirements. Cities with exceedingly rigid designs leave little room for them to evolve.

The unité model generates segregation

Far from promoting coexistence based on the mixed uses idea, which the architect had planned for his unité d’habitation, experience tells us that these large blocks of apartments eventually become warrens, where insecurity ends up being rife.

Zoning, yes but…

Organizing the programs to be developed in the city by zones is an efficient method, but it also pigeonholes zones and prevents spaces from being created that foster and feature the diversity of the neighborhoods that make up our cities.

Photos | Ricardo Rodríguez, Tamaño y densidad urbana: análisis de la ocupación de suelo por las áreas urbanas españolas, La Ville Radieuse de Le Corbusier : les paradoxes d’une utopie de la société machiniste, The Charnel-House

Tomorrow.Building (7-9 November, Barcelona, in parallel with the Smart City Expo) is the new global initiative empowering the green and digital transition of buildings and urban infrastructures. Discover more at https://www.tomorrow-building.com/.