Author | Marcos MartínezJakarta, the Indonesian capital, is sinking. 10.1 million people lived in the city in 2017, and over 30 million in its metropolitan area. As a solution to combat the rising seal-levels due to climate change, the state plans to move the capital, according to the minister Bambang Brodjonegoro. But the sinking city is not just due to rising sea levels.Jakarta was built on swampy ground, making it unstable. The over-extraction of groundwater has also weakened the aquifers. We are all responsible for the last blow with climate change. According to some forecasts, the city will disappear by 2050 and these types of events could occur more often. Efficient water management is essential to combat climate change.

A dreadful water policy

As mentioned earlier, Jakarta is a city built on a swamp. It is not the only city to be built on water or the first to encounter problems resulting from this. The Aztecs in pre-Hispanic America drained the Texcoco Lake to build the city of Tenochtitlan around the 14th century; while Venice was built on around 120 islands in the 5th century. Today Mexico DF suffers worse earthquakes and Venice is sinking.If in Jakarta the final blow came with climate change, which is also threatening to do away with Venice’s heritage, as we will see later, in Mexico DF, the problem arose when, during the 16th century, the settlers drained Tenochtitlan. We now know that this is having a significant impact on earthquakes, with these increasing as a result of the clay sediments that were left behind. Earthquakes and flooding do not appear to be related, yet both Mexico and Jakarta have a common denominator; a dreadful water policy. In the Indonesian city, the problem was aggravated for decades because of the construction of illegal wells that drain the aquifers.In addition, the concrete in the city of Jakarta covers such a vast area that the water cannot get through it. The entire city acts as a protective crust, and the aquifers do not fill up, as reported by Fluence. As a result, the city’s foundations are gradually weakening. In dry countries this water extraction leads to serious droughts.

Earthquakes and flooding do not appear to be related, yet both Mexico and Jakarta have a common denominator; a dreadful water policy. In the Indonesian city, the problem was aggravated for decades because of the construction of illegal wells that drain the aquifers.In addition, the concrete in the city of Jakarta covers such a vast area that the water cannot get through it. The entire city acts as a protective crust, and the aquifers do not fill up, as reported by Fluence. As a result, the city’s foundations are gradually weakening. In dry countries this water extraction leads to serious droughts.

When the ground moves, infrastructures collapse

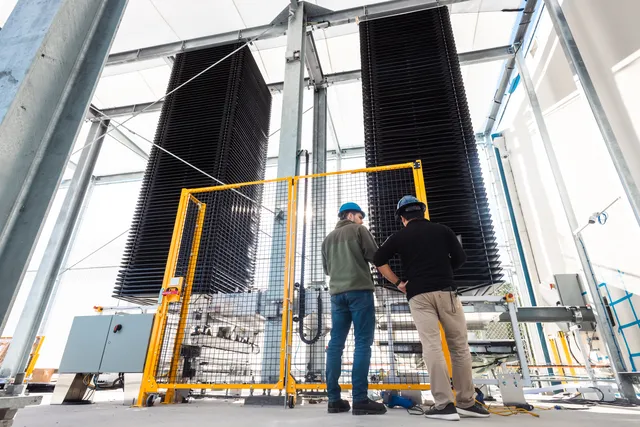

But Jakarta, Mexico or Venice are not the only cities in the world whose foundations are suffering as a result of human activity. In a considerable part of Russia, Alaska, China and Canada, they are experiencing serious problems with basic infrastructures such as railway lines. Remember, the most efficient mass transit option. The problem occurs when the permafrost heats up.The permafrost is a type of soil in which the “active layer”, a layer four centimetres from the surface, remains frozen all year round. It is a fantastic material for building on given its stability, but global heating is making it melt. As the climate expert, Laurence C. Smith, stated in his book ‘The World in 2050’, “the substrate acquires the structural resistance of wet clay”.Railway lines cannot be built on clay. Nor homes, hospitals or schools. The Winnipeg-Churchill (Canada) train was affected back in 2010, when it had to reduce its speed for a number of kilometres. The Qinghai-Tibet railway line, on the Tibetan Plateau between Goldmud and Lhasa, was also affected. The same occurred between Baikal and Amur in Russia. In 2005, the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment published a document that revealed very worrying details such as those above. If sustainable rail transport is compromised, many will choose to use polluting air travel, worsening the emissions problem.The ACIA also referred to cities in its report. The percentage of dangerous buildings in large towns and cities ranges from 22% in Tiksi (Arctic) and 80% in Vorkuta (Russia). Let’s just imagine for a second, what it means for a city when four out of five buildings are on the verge of collapse. This is what will happen in the Mediterranean, but with entire cities.Meanwhile, according to Suez, with develops and markets its own smart irrigation and urban drainage technologies, "the needs of agriculture account for 70% of the water consumed worldwide". And while industrial usage may seem a small amount in light of this, the company expects that the latter will account for 22% of all water consumption in 2030. Developing countries are facing now a double challenge: dealing with the realities of climate change and addressing the requirements of economies still vastly dependent on agriculture, yet quickly moving towards industrialisation. Water sources will be under severe strain… and in dire need of proper management.

In 2005, the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment published a document that revealed very worrying details such as those above. If sustainable rail transport is compromised, many will choose to use polluting air travel, worsening the emissions problem.The ACIA also referred to cities in its report. The percentage of dangerous buildings in large towns and cities ranges from 22% in Tiksi (Arctic) and 80% in Vorkuta (Russia). Let’s just imagine for a second, what it means for a city when four out of five buildings are on the verge of collapse. This is what will happen in the Mediterranean, but with entire cities.Meanwhile, according to Suez, with develops and markets its own smart irrigation and urban drainage technologies, "the needs of agriculture account for 70% of the water consumed worldwide". And while industrial usage may seem a small amount in light of this, the company expects that the latter will account for 22% of all water consumption in 2030. Developing countries are facing now a double challenge: dealing with the realities of climate change and addressing the requirements of economies still vastly dependent on agriculture, yet quickly moving towards industrialisation. Water sources will be under severe strain… and in dire need of proper management.

Cities that will sink in the Mediterranean

In 1953, the Netherlands suffered such destructive floods that in 1987 they built the Oosterscheldekering, an eight-kilometre-long barrier between the islands of Schouwen-Duiveland and Noord-Beveland, considered to be the world’s first flood barrier. A plaster to combat climate change and a (slight) increase in resilience.In 2018, it became clear that all these measures were inefficient in the long term. The models indicate that the whole of the Netherlands is gradually sinking. In 1982, the Thames one was completed in London, but the city is heading the same way as the Netherlands. Shanghai, Houston, Bangkok and other cities “may seem strong and stable, but it is a mirage”, according to Kat Kramer, a contributor to the Christian Aid report which the BBC helped broadcast in 2018. The Venetian Lagoon and its city, may not be so lucky. According to a report drawn up by the MedECC (Mediterranean Experts on Climate and Environmental Change), “500 million inhabitants will have to adapt to almost inevitable changes”. It is estimated that by 2100, the Mediterranean sea level will have risen by one metre and temperatures will rise by four degrees. Scientific reports corroborate this.Wedges to raise buildings are not enough to combat the rising level of the Mediterranean. Valencia (Spain), Cesme (Greece) or Mersin (Turkey), are some of the cities threatened by the rising levels of the Mediterranean. Climate models were wrong and climate change is occurring at a much faster rate than we imagined. Can we adapt cities to the new crisis?

The Venetian Lagoon and its city, may not be so lucky. According to a report drawn up by the MedECC (Mediterranean Experts on Climate and Environmental Change), “500 million inhabitants will have to adapt to almost inevitable changes”. It is estimated that by 2100, the Mediterranean sea level will have risen by one metre and temperatures will rise by four degrees. Scientific reports corroborate this.Wedges to raise buildings are not enough to combat the rising level of the Mediterranean. Valencia (Spain), Cesme (Greece) or Mersin (Turkey), are some of the cities threatened by the rising levels of the Mediterranean. Climate models were wrong and climate change is occurring at a much faster rate than we imagined. Can we adapt cities to the new crisis?

Urban resilience is crucial

The Sustainable Development Goal Number 11 refers to Sustainable cities and communities’, focusing on them being “more inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”. Resilience is the capacity of communities and ecosystems to undergo disturbance without shifting to an alternative state. It is a capacity we are losing in the fight against climate change.Railway lines were resilient to the forces twenty years ago, but not to the ones of today. In order to be resilient, we need to adapt cities and change citizens’ habits. Instead of travelling by plane, car or motorbike, we need to choose more sustainable forms of transport and we need to promote rational use of resources. They have not done this in Jakarta.Images| iStock/CreativaImages, iStock/andyparker72, iStock/Nordroden, iStock/IR_Stone