Author | M. Martínez Euklidiadas

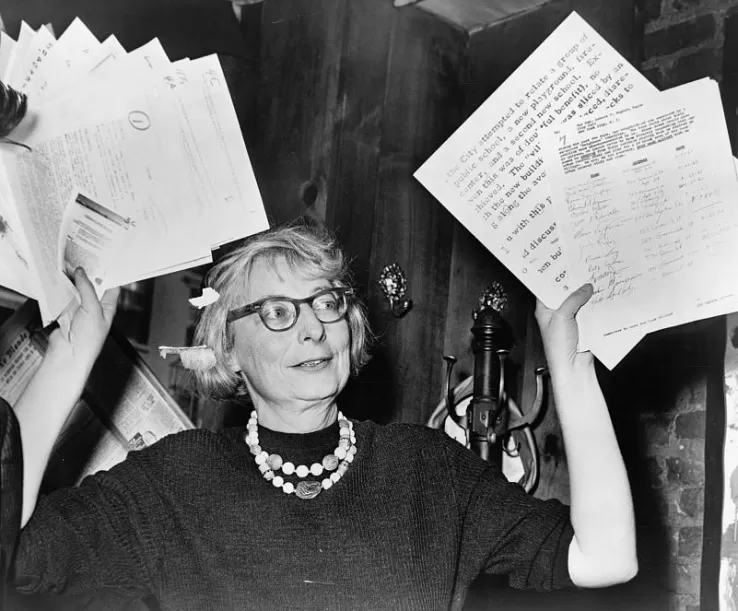

For hundreds of years the Turkish Cappadocia was home to dozens of small subterranean communities, where families lived their lives and prospered. Elengubu, now known as Derinkuyu, was a massive underground city, with 11 levels, some reaching depths of 85 meters, and with the capacity to accommodate up to 20,000 people. Why did they live like this?

Due to the passage of time and lack of historical records, Derinkuyu remains an unknown and mysterious city. It is not exactly clear how its inhabitants lived, why they lived underground or what made them originally dig down beneath the ground. There are also some doubts as to how the tunnels were built and how residents were able to organize themselves.

Cappadocia, a unique region of the world

The region of Cappadocia, which does not officially exist as such in Turkey, is a 25-km radius circular region with a unique geology thanks to the ancient volcanic activity in the area. The entire area is full of natural galleries carved out to generate vast spaces underground.

The fairy chimneys are one of the tourist attractions visible above ground, while below ground, dozens of settlements are waiting to be discovered by speleologists. The pitted landscape of Derinkuyu spent a great deal of time in darkness, unaltered since it was abandoned in 1923.

The unexpected discovery of Derinkuyu

In 1963, the owner of one of the cave houses in what is now Derinkuyu, was extending his property, when he accidently demolished what he thought to be a rock wall and it turned out to be a wall separating a room. There was a room on the other side of the wall which, in turn led through to another. Today, only 10% of the city is accessible to tourists. The rest is still being explored.

What was vertical urbanism like in Derinkuyu?

A whole host of professions and activities took place within the city of Derinkuyu. Stables, wine cellars, mills, taverns, wells, forges, houses, silos, markets, wineries and oil mills, sheds, schools, chapels and refectories and meeting rooms or forums have been found. It is clear that the residents of Elengubu were well organized. But, what was its urbanism and resilience-based architecture like?

Today, the ‘negative space’ of urbanism—the physical free space not occupied by buildings or facilities— is mainly air. It is possible, for example to look from one end of a street to another or see what is happening various blocks away. In the depths of Elengubu, there was no negative space and no windows. It was a very different type of urbanism to what we know today.

In the academy, this type of troglodyte construction —Τρωγλοδύται, literally "cave goers"— involves digging horizontally into the rock, an extraction activity that consists of hollowing out the mountain. The first houses are thought to have been dug into the side of the mountains (photograph above), and due to a lack of space, they began digging more levels below, through vertical excavation (photograph below)

Elengubu, a dozen cities

It is important to add that Elengubu is not a single city, and it was not always the same city. Throughout the centuries, it underwent striking transformations, some of which were quite significant. For example, vertical shafts that existed from the start were made wider (photograph above) and could sometimes even accommodate freight elevators. Up to 52 vertical shafts and more than 15,000 ‘small’ ventilation shafts have been catalogued.

One of the most important defensive transformations took place during the Byzantine Empire, when all the entrances, where guards would be positioned, were modified to install enormous stone doors, which were closed from inside. The city was then ironclad.

The construction of underground wells took place over various decades. As the city’s population and cattle increased, more openings towards the phreatic zone that contained water had to be made.

The exact century in which a 9-km tunnel between Kaymakli and Elengubu was built is not known, but what is known is that the Christians often used it when they invaded the cities. In the past it was not exactly easy to besiege two cities at once, and the tunnel served as an escape route from one city to another.

An interesting fact is that the food destined for human consumption was kept away from animals, as well as food preparation processes. For example, bakeries. The city’s social organization entailed a high degree of hygiene, which was essential for cave life.

How did they excavate Derinkuyu?

It is not exactly clear why the Phrygians from the 8th and 7th century BCE started to perforate the city of Elengubu through the volcanic rocks. Furthermore, the first inhabitants may have been Hittites from around the 17^th^ century BCE. And there are some theories that the first caves on the side of the mountain may have been from the ninth millennium before the common era (BCE), coinciding with a glaciation.

What is certain is that in the meantime they were inhabited by Greeks, Romans and Christians, given the construction methods used inside the caves. Nearly all the villages in the region have been inhabited in one way or another, and like any other human settlement, they have changed with the different cultures.

It is often said that even with today’s technology, it would be hard to replicate the city of Derinkuyu. This is not entirely true, it is actually a similar issue to that of sending more humans to the Moon. Now safety is greater and costs extremely high. When we can build on the surface, there is no need and no resources to dig out cities. And no use. It is energetically more expensive.

Images | Nevit Dilmen, Bhumil Chheda, Travel Turkey/Shutterstock, katesid/Shutterstock