Author | Lucía Burbano

The term ‘Doughnut Economics’ was first coined by the British economist Kate Raworth in a report published in Oxfam in 2012 and which she subsequently continued to develop in her book ‘Doughnut Economics: seven ways to think like a 21st century economist’. In both, she proposes a new humanist economic model, a tool which many cities worldwide are starting to use.

What is the doughnut theory or the theory of Doughnut economics?

The theory of the Doughnut formula is a change of economic model as a response to humanity’s major challenge: eradicating global poverty all within the means of the planet’s limited natural resources.

It receives this name because it is visually represented by two doughnut-shaped discs: the one in the center is the social foundation, which includes basic fundamental rights, and the outer ring is the ecological ceiling, which cannot be exceeded if we are to guarantee the prosperity of humanity. In the middle would be the doughnut, understood as the space in which humanity can progress if the planet’s boundaries are respected. Both circumferences coincide with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

This change of paradigm proposes shifting from an economic model of constant growth measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and realizing that, in the end, economic prosperity depends on human and natural wellbeing. To achieve this, it proposes transforming governance systems, making these regenerative and distributive instead of finite and egotistical.

What are the limits of the Doughnut model in order to prosper?

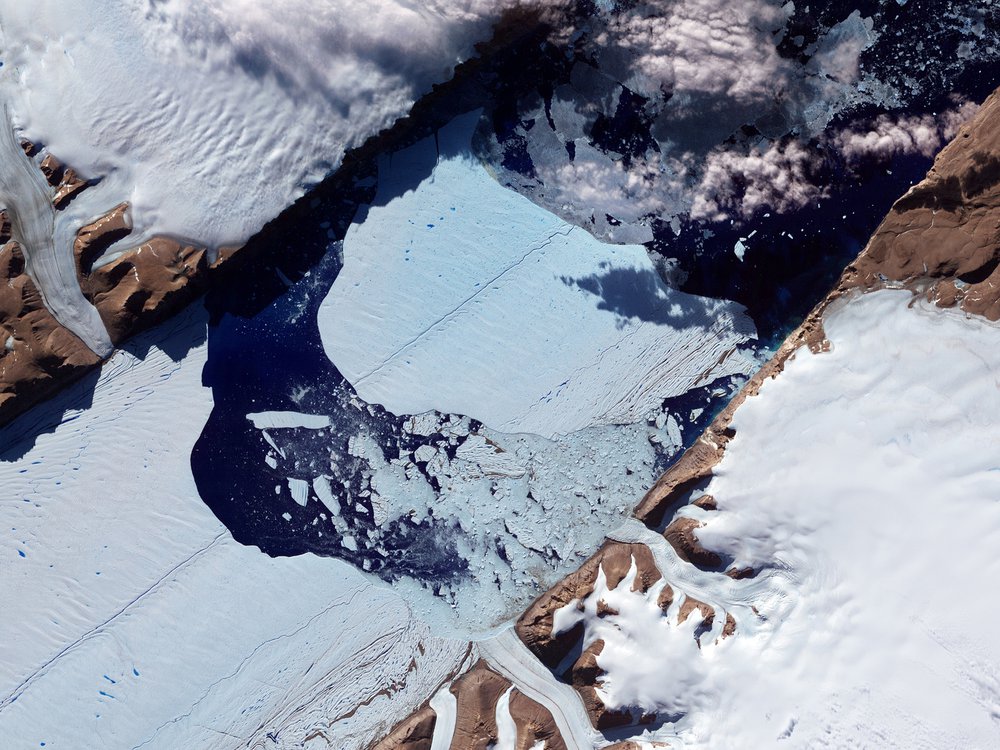

The economist identifies nine environmental thresholds that should not be exceeded in order to avoid further natural degradation that jeopardizes the health of the Planet even more: climate change, biodiversity loss, ocean acidification, land conversion, freshwater withdrawals, nitrogen and phosphorus loading, chemical pollution, air pollution and ozone layer depletion.

In turn, there are 12 essential social goals for humanity to prosper, many of which are basic human rights: food safety, a living income, water and sanitation, healthcare, education, energy, gender equality, social equity, resilience, participation, employment, networks and access to housing.

Real-world economies

Doughnut economics is a relatively new and highly experimental concept. As such, there are no case studies to look after, although several cities are looking into the theory in order to build back after the COVID-19 pandemic and increase their resilience.

- Amsterdam: The capital of the Netherlands has already announced that it will embrace doughnut economics as part of their COVID-19 recovery plan. Some of its projects involve the construction of six new islands reclaimed from the sea using foundations that respect the local wildlife, setting new standards for circular use of materials in major works involving city-owned buildings (including a fairly novel materials passport to enable their reuse) and a campaign to provide computer-less residents with proper PCs using donated and refurbished laptops, allowing them to access all kinds of services during lockdowns and other emergencies. On top of that, Amsterdam wants a 50% reduction of food waste by 2030 and promote second-hand shows in order to reduce needless consumption.

- Brussels: The Brussels Region, in neighboring Belgium, is also giving doughnut economics a go. A highly cosmopolitan but also unequal metropolis, is testing the theory at micro and nano scale by refurbishing the old and abandoned mint of the Ministry of Finance, "minimizing the environmental impacts and maximizing the social impacts". Its large premises, with 4,000 square-meters of space, will be made available to Zinneke, an NGO promoting the arts. The Arc-en-Ciel housing project in Molenbeek is probably more interesting. Originally constructed in 2018, this building is meant to offer affordable and accessible housing through common property ownership. Its inhabitants were allowed to design and build it according to the code, while the apartments have a very small carbon footprint due to the use of a passive thermal regulation system.

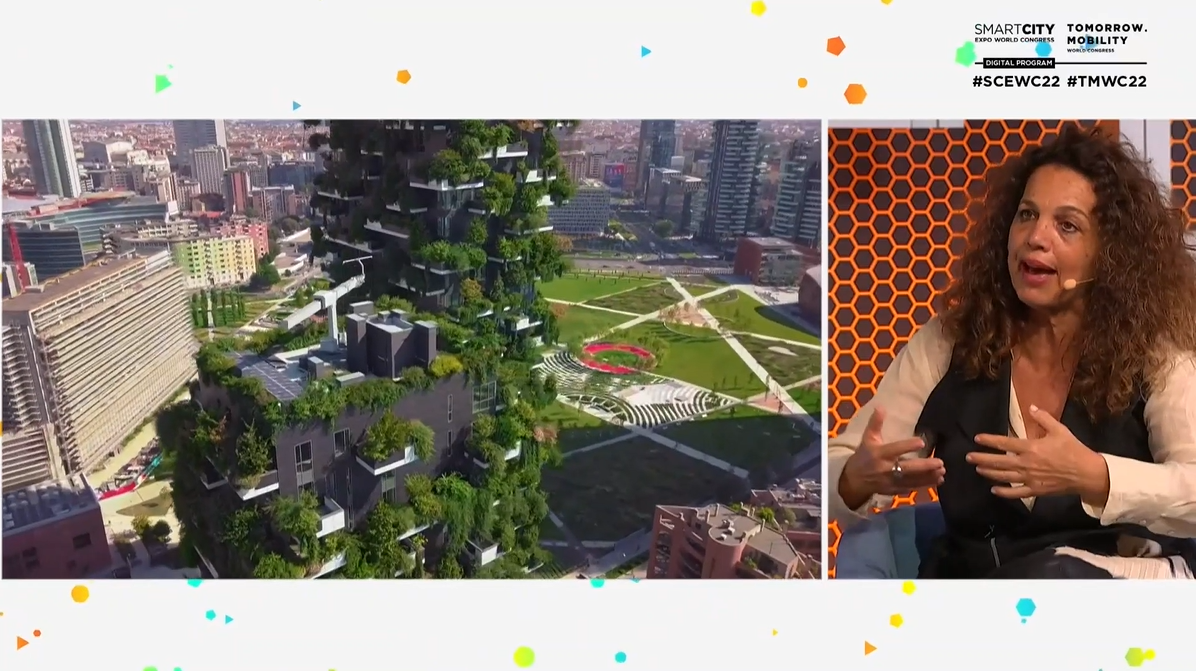

How can this theory alleviate life in cities?

Cities can act as transforming agents of this change proposed by Raworth. Amsterdam, Brussels, Melbourne or Berlin are examples of cities joining the "doughnut effect" and are thus paving the way towards social and environmental sustainability. The starting point for all of them is similar: initiate broader participatory processes to identify possible solutions to their most pressing problems.

In order to incorporate the doughnut into their urban management models, cities must answer the following questions:

- Objective: What or who does the city serve?

- Networks: How is the city using its purchasing power and its networks?

- Governance: How is the city governed? Who is included in decision-making processes?

- Ownership? Who owns the city’s sources of wealth?

- Finances: Are the finances at the service of the city or the city at the service of the finances?

An example is Amsterdam which, after conducting this exercise, came face to face with the harsh reality: 20% of tenants cannot even cover their basic needs after paying their rent. Although the most obvious solution would be to build more houses, the city’s CO2 emissions are 31% higher than they were in 1990. The strategy they have come up with to counteract the two problems is to implement laws making the use of recycled and natural materials mandatory in the construction sector.

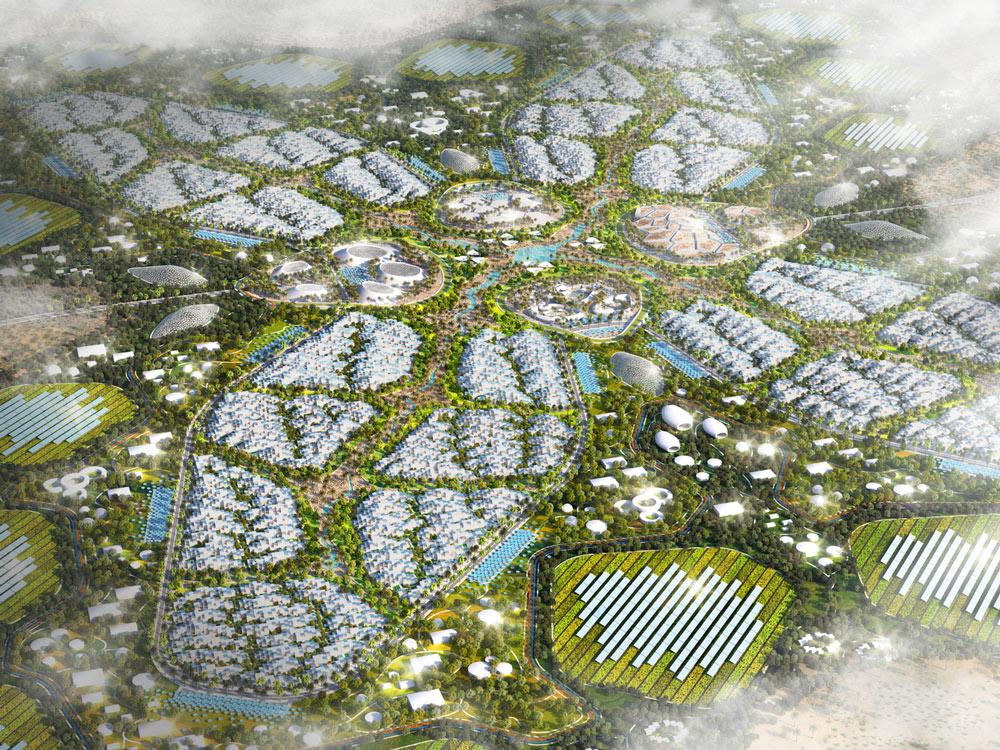

Melbourne’s Doughnut model

Melbourne’s Doughnut model

Criticisms of the doughnut model

The economist Branko Milanovic is one of the theory’s main skeptics, arguing that Raworth’s model does not take into account aspects such as the fact that without greater GDP growth, we will not eradicate global poverty. Likewise, current sustainable innovations are marginal and their progress is minimal compared with "what should happen".

Finally, Milanovic considers the book to portray globalized capitalism as entering into a "more cooperative and gentler phase", but in reality, citizens are becoming more commercially motivated, which is leading towards a self-centered, money- and success-oriented society, while transmitting a world that is "devoid of major social contradictions", and says there is no "we" that includes 7.3 billion people. Different class and national interests are fighting each other.

As tends to be the case with global development models, the one advocated by the doughnut theory sets out well-identified problems and their possible solutions, but that does not mean they are going to be true or applicable worldwide.

Without a series of universal solutions, which do not exist and will probably not exist, it will be up to the politicians and economists to assess whether it can be implemented successfully and, if so, to what extent.

Images | Unsplash/Patrick Fore, Arts and Craft/Doughnut Economics Action Lab, Sean Trewick/Regen Melbourne